| Table of Contents |

|---|

...

| Expand | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

If your Windows version does not have ssh in Command Prompt or PowerShell:

More advanced options for those who want a full Linux environment on their Windows system:

|

From now on, when we refer to "Terminal", it is either the Mac/Linux Terminal program, Windows Command Prompt or PowerShell, or the PuTTY program.

...

- Answer yes to the SSH security question prompt

- this will only be asked the 1st time you access ls6

- Enter the password associated with your TACC account

- for security reasons, your password characters will not be echoed to the screen

- Get your 2-factor authentication code from your phone's TACC Token app, and type it in

| Expand | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

If you're using PuTTY as your Terminal from Windows:

|

...

There are many shell programs available in Linux, but the default is bash (Bourne-again shellBourne-again shell).

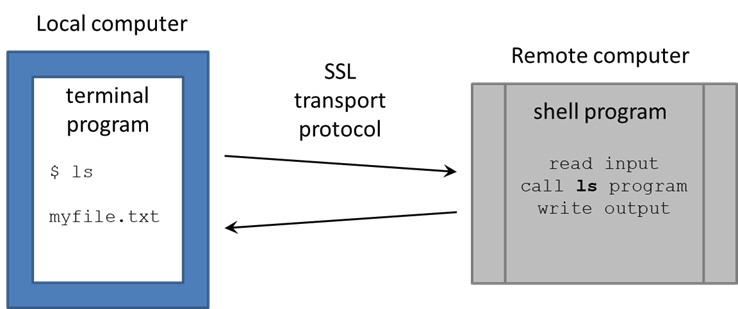

The Terminal is pretty "dumb" – just sending what you type over its secure sockets layer (SSL) connection to TACC, then displaying the text sent back by the shell. The real work is being done on the remote computer, by executable programs called by the bash shell (also called commands, since you call them on the command line).

About the command line

Read more about the command line and commands on our Linux fundamentals page:

When you type something in at a bash command-line prompt, it Reads the input, Evaluates it, then Prints the results, then does this over and over in a Loop. This behavior is called a REPL – a Read, Eval, Print Loop.

Many programming language environments have REPLs – Python and R for example. The input to the bash REPL is a command. Here are some examples:

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

ls # example 1 - no options or arguments

ls -l # example 2 - one "short" (single character) option only (-l)

ls --help # example 3 - one "long" (word) option (--help)

ls .profile # example 4 - one argument, a file name (.profile)

ls --width=20 # example 5 - a long option that has a value (--width is the option, 20 is the value)

ls -w 20 # example 6 - a short option w/a value, as above, where -w is the same as --width

ls -l -a -h # example 7 - three short options entered separately (-l -a -h)

ls -lah # example 8 - three short options that can be combined after a dash (-lah) |

A command consists of:

- The command name – here ls (list files)

- A command can be any of the built-in Linux/Unix commands, or the name of a user-written script or program

- One or more options, usually noted with a leading dash (-) or double-dash (--).

- -l in example 2 (long listing)

- --help in example 3

- Options are optional – they do not have to be supplied (e.g. example 1 above)

- One or more command-line arguments, which are often (but not always) file names

- e.g. .profile in example 4

The shell executes the command line input when it sees a linefeed, which happens when you press Enter after entering the command.

Command options

The notes below apply to nearly all built-in Linux utilities, and to many 3rd party programs as well

- Short (1-character) options can be provided separately, prefixed by a single dash(-)

- or can be combined with the combination prefixed by a single dash (examples 7, 8)

- Long (multi-character/"word") options are prefixed with a double dash (--) and must be supplied separately.

- Many utilities have equivalent long and short options (e.g. --width and -w above)

- Both long and short options can be assigned a value (examples 5, 6)

- The short option and its value are usually separated by a space, but can also be run together (e.g. -w20)

- Strictly speaking, the long option and its value should be separated by an equal sign (=) according to the POSIX standard (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/POSIX). But many programs let you use a space as separator also.

Some handy options for ls:

- -l shows a long listing, including file permissions, ownership, size and last modified date.

- -a shows all files, including dot files whose names start with a period ( . ) which are normally not listed

- -h says to show file sizes in human readable form (e.g. 12M instead of 12201749)

The arguments to ls are one or more file/directory names. If no arguments are provided, the contents of the current directory are listed. If an argument is a directory name, the contents of that directory are listed.

Getting help

So how do you find out what options and arguments a command uses?

- In the Terminal, type in the command name then the --help long option (e.g. ls --help)

- Works for most Linux commands; 3rd party tools may use -h or -? or even /? instead

- May produce a lot of output, so you may need to scroll up quite a bit or pipe the output to a pager (e.g. ls --help | more)

- Use the built-in manual system (e.g. type man ls)

- This system uses the less pager that we'll go over later.

- For now, just know that a space advances the output by one screen/"page", and typing q will exit the display.

- Ask the Google, e.g. search for ls man page

- Can be easier to read

Every Linux command has tons of options, most of which you'll never use. The trick is to start with the most commonly used options and build out from there. Then, if you need a command to do something special, check if there's an option already to do that.

A good place to start learning built-in Linux commands and their options is on our Linux fundamentals page.

Setting up your environment

Setup your login profile (~/.bashrc)

Now execute the lines below to set up a login script, called ~/.bashrc

When you login via an interactive shell, a well-known script is executed to establish your favorite environment settings. The well-known filename is ~/.bashrc (or ~/.profile on some systems), which is specific to the bash shell.

We've set up a common login script for you to start with that will help you know where you are in the file system and make it easier to access some of our shared resources. To set it up, perform the steps below:

| Tip |

|---|

You can copy and paste these lines from the code block below into your Terminal window. Just make sure you hit Enter after the last line. |

| Warning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

If you already have a .bashrc set up, make a backup copy first.

You can restore your original login script after this class is over. |

If your Terminal has a dark background (e.g. black), copy this file:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

cp /corral-repl/utexas/BioITeam/core_ngs_tools/login/bashrc.corengs.ls6.dark_bg ~/.bashrc

chmod 600 ~/.bashrc |

If your Terminal has a light background (e.g. white), copy this file:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

cp /corral-repl/utexas/BioITeam/core_ngs_tools/login/bashrc.corengs.ls6.light_bg ~/.bashrc

chmod 600 ~/.bashrc |

So why don't you see the .bashrc file you just copied to your home directory when you do ls? Because all files starting with a period (dot files) are hidden by default. To see them add the -l (long listing) and -a (all) options to ls:

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

# show a long listing of all files in the current directory, including "dot files" that start with a period

ls -la |

| Expand | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

What's going on with chmod? The chmod 600 ~/.bashrc command marks the file as readable and writable only by you. |

Since your ~/.bashrc is executed when you login, to ensure it is set up properly you should first log off ls6 like this:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

exit |

Your Terminal has logged off of Lonestar6 and is now back on your local computer.

Now log back in to ls6.tacc.utexas.edu. This time your ~/.bashrc will be executed to establish your environment:

| Tip | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Your new ~/.bashrc file defines a ll alias command, so when you type ll it is short for ls -la. |

You should see a new command line prompt:

| Code Block |

|---|

ls6:~$ |

The great thing about this prompt is that it always tells you where you are, which avoids you having to execute the pwd (present working directory) command every time you want to know what the current directory is. Execute these commands to see how the prompt reflects your current directory.

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

mkdir -p ~/tmp/a/b/c

cd ~/tmp/a/b/c

# Your prompt should look like this:

ls6:~/tmp/a/b/c$ |

The prompt now tells you you are in the c sub-directory of the b sub-directory of the a sub-directory of the tmp sub-directory of your Home directory ( ~ ).

Your login script has configured this command prompt behavior, along with a number of other things.

Details about your login script

Let's take a look at the contents of your ~/.bashrc login script, using the cat (concatenate files) command. cat simply reads a file and writes each line of content to standard output (here, your Terminal):

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

cd

cat .bashrc

|

| Tip | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

The cat command just displays the entire file's content, line by line, without pausing, so should not be used to display large files. Instead, use a pager (like more or less) or look at parts of the file with head or tail. |

You'll see the following (you may need to scroll up a bit to see the beginning):

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

#!/bin/bash

# TACC startup script: ~/.bashrc version 2.1 -- 12/17/2013

# This file is NOT automatically sourced for login shells.

# Your ~/.profile can and should "source" this file.

# Note neither ~/.profile nor ~/.bashrc are sourced automatically

# by bash scripts.

# In a parallel mpi job, this file (~/.bashrc) is sourced on every

# node so it is important that actions here not tax the file system.

# Each nodes' environment during an MPI job has ENVIRONMENT set to

# "BATCH" and the prompt variable PS1 empty.

#################################################################

# Optional Startup Script tracking. Normally DBG_ECHO does nothing

if [ -n "$SHELL_STARTUP_DEBUG" ]; then DBG_ECHO "${DBG_INDENT}~/.bashrc{"; fi

##########

# SECTION 1 -- modules

if [ -z "$__BASHRC_SOURCED__" -a "$ENVIRONMENT" != BATCH ]; then

export __BASHRC_SOURCED__=1

module load launcher

fi

############

# SECTION 2 -- environment variables

if [ -z "$__PERSONAL_PATH__" ]; then

export __PERSONAL_PATH__=1

export PATH=.:$HOME/local/bin:$PATH

fi

# For better colors using a dark background terminal, un-comment this line:

#export LS_COLORS=$LS_COLORS:'di=1;33:fi=01:ln=01;36:'

# For better colors using a white background terminal, un-comment this line:

#export LS_COLORS=$LS_COLORS:'di=1;34:fi=01:ln=01;36:'

export LANG="C" # avoid the annoying Perl locale warnings

export BIWORK=/work/projects/BioITeam

export CORENGS=$BIWORK/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools

export BI=/corral-repl/utexas/BioITeam

export ALLOCATION=OTH21164 # For ls6 Group is G-824651

##export ALLOCATION=UT-2015-05-18 # For stampede2 Group is G-816696

##########

# SECTION 3 -- controlling the prompt

if [ -n "$PS1" ]; then PS1='ls6:\w$ '; fi

##########

# SECTION 4 -- Umask and aliases

#alias ls="ls --color=always"

alias ll="ls -la"

alias lah="ls -lah"

alias lc="wc -l"

alias hexdump='od -A x -t x1z -v'

umask 002

##########

# Optional Startup Script tracking

if [ -n "$SHELL_STARTUP_DEBUG" ]; then DBG_ECHO "${DBG_INDENT}}"; fi |

There's a lot of stuff here; let's look at just a few things.

environment variables

The login script sets several environment variables.

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

export BIWORK=/work/projects/BioITeam

export CORENGS=$BIWORK/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools

export ALLOCATION=OTH21164 |

Environment variables are like variables in other programming languages like python or perl (in fact bash is a complete programming language).

They have a name (like BIWORK above) and a value (the value of $BIWORK is the pathname of the shared /work/projects/BioITeam directory). Read more about environment variables here: More on environment variables.

To see the value of an environment variable, use the echo command, then the variable name after a dollar sign ( $ ):

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

echo $CORENGS

echo $ALLOCATION |

Environment variables are like variables in a programming language like python or perl (in fact bash is a complete programming language). They have a name (like BIWORK above) and a value (the value of $BIWORK is the pathname /work/projects/BioITeam). Read more about environment variables here: More on environment variables.

shell completion

You can use these environment variables to shorten typing, for example, to look at the contents of the shared /work/projects/BioITeam directory as shown below, using the magic Tab key to perform shell completion.

| Tip | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

The Tab key is one of your best friends in Linux. Hitting it invokes shell completion, which is as close to magic as it gets!

|

Follow along with this:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

# hit Tab once to expand the environment variable name

ls $BIW

# hit Tab again to expand the environment variable

ls $BIWORK/

# now hit Tab twice to see the contents of the directory

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/

# type "pr" and hit Tab again

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/pr

# type "co" and hit Tab again

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/co

# type "Co" and hit Tab again

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Co

# your command line should now look like this

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/

# now type "mi" and one Tab

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/mi

# your command line should now look like this

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/misc/

# now hit Tab once

# There is no unambiguous match, so hit Tab again

# After hitting Tab twice you should see several filenames:

# fastqc/ small.bam small.fq small2.fq

# now type "sm" and one Tab

# your command line should now look like this

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/misc/small

# type a period (".") then hit Tab twice again

# You're narrowing down the choices -- you should see two filenames

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/misc/small

# small.bam small.fq

# finally, type "f" then hit Tab again. It should complete to this:

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/misc/small.fq |

extending the $PATH

When you type a command name the shell has to have some way of finding what program to run. The list of places (directories) where the shell looks is stored in the $PATH environment variable. You can see the entire list of locations by doing this:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

echo $PATH

|

As you can see, there are a lot of locations on the $PATH. That's because when you load modules at TACC (such as the module load lines in the common login script), that makes the programs available to you by putting their installation directories on your $PATH. We'll learn more about modules later.

Here's how the common login script adds your $HOME/local/bin directory to the location list (we'll create that directory shortly), along with a special dot character ( . ) that means "here", or "whatever the current directory is". In the statement below, colon ( : ) separates directories in the list.

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

export PATH=.:$HOME/local/bin:$PATH

|

setting up the friendly command prompt

The complicated looking if statement in SECTION 3 of your .bashrc sets up a friendly shell prompt that shows the current working directory. This is done by setting the special PS1 environment variable and including a special \w directive that the shell knows means "current directory".

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

##########

# SECTION 3 -- controlling the prompt

if [ -n "$PS1" ]; then PS1='ls6:\w$ '; fi

|

Create some symbolic links and directories

Create some symbolic links that will come in handy later:

...

| language | bash |

|---|---|

| title | Create symbolic directory links |

...

Setting up your environment

Setup your login profile (~/.bashrc)

Now execute the lines below to set up a login script, called ~/.bashrc. [ Note the tilde ( ~ ) is shorthand for "my Home directory". See Linux fundamentals: Pathname syntax ]

When you login via an interactive shell, a well-known script is executed to establish your favorite environment settings. The well-known filename is ~/.bashrc (or ~/.profile on some systems), which is specific to the bash shell.

We've pre-created a common login script for you that will help you know where you are in the file system and make it easier to access some of our shared resources. To set it up, perform the steps below:

| Tip |

|---|

You can copy and paste these lines from the code block below into your Terminal window. Just make sure you hit Enter after the last line. |

| Warning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

If you already have a .bashrc set up, make a backup copy first.

You can restore your original login script after this class is over. |

If your Terminal has a dark background (e.g. black), copy this file:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

cp /corral-repl/utexas/BioITeam/core_ngs_tools/login/bashrc.corengs.ls6.dark_bg ~/.bashrc

chmod 600 ~/.bashrc |

If your Terminal has a light background (e.g. white), copy this file:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

cp /corral-repl/utexas/BioITeam/core_ngs_tools/login/bashrc.corengs.ls6.light_bg ~/.bashrc

chmod 600 ~/.bashrc |

So why don't you see the .bashrc file you just copied when you do ls? Because all files starting with a period (dot files) are hidden by default. To see them add the -l (long listing) and -a (all) options to ls:

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

# show a long listing of all files in the current directory, including "dot files" that start with a period

ls -la |

Read more about File attributes

| Expand | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

What's going on with chmod? The chmod 600 ~/.bashrc command marks the file as readable and writable only by you. |

Since your ~/.bashrc is executed when you login, to ensure it is set up properly you should first log off Lonestar6 like this:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

exit |

Your Terminal has logged off of Lonestar6 and is back on your local computer.

Now log back in to ls6.tacc.utexas.edu. This time your ~/.bashrc will be executed to establish your environment:

| Tip | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Your new ~/.bashrc file defines a ll alias command, so when you type ll it is short for ls -la. |

You should see a new command line prompt:

| Code Block |

|---|

ls6:~$ |

The great thing about this prompt is that it always tells you where you are, which avoids you having to execute the pwd (present working directory) command every time you want to know what the current directory is. Execute these commands to see how the prompt reflects your current directory.

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

# mkdir -p says to create all parent directories in the specified path

mkdir -p ~/tmp/a/b/c

cd ~/tmp/a/b/c

# Your prompt should look like this:

ls6:~/tmp/a/b/c$ |

The prompt now tells you you are in the c sub-directory of the b sub-directory of the a sub-directory of the tmp sub-directory of your Home directory ( ~ ).

Your login script has configured this command prompt behavior, along with a number of other things.

Create some symbolic links and directories

Create some symbolic links that will come in handy later:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

cd # makes your Home directory the "current directory"

ln -s -f $SCRATCH scratch

ln -s -f $WORK work

ln -sf /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools CoreNGS

ls # you'll see the 3 symbolic links you just created

|

Symbolic links (a.k.a. symlinks) are "pointers" to files or directories elsewhere in the file system hierarchy. You can almost always treat a symlink as if it is the actual file or directory.

| Tip |

|---|

$WORK and $SCRATCH are TACC environment variables that refer to your Work and Scratch file system areas – more on these file system areas soon. (Read more about Environment variables) |

| Expand | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

The ln -s command creates a symbolic link, a shortcut to the linked file or directory.

Want to know where a link points to? Use ls with the -l (long listing) option.

|

Set up a ~/local/bin directory and link a script there that we will use in the class.

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

mkdir -p ~/local/bin

cd ~/local/bin

ln -s -f /work/projects/BioITeam/common/bin/launcher_creator.py

|

Since our ~/.bashrc login script added ~/local/bin to our $PATH, we can call any script or command in that directory with just its file name. And Tab completion works on program names too:

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

cd

# hit Tab once after typing "laun"

# This will expand to launcher_creator.py

|

Details about your login script

Let's take a look at the contents of your ~/.bashrc login script, using the cat (concatenate files) command. cat simply reads a file and writes each line of content to standard output (here, your Terminal):

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

cd

cat .bashrc

|

| Tip | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

The cat command just displays the entire file's content, line by line, without pausing, so should not be used to display large files. Instead, use a pager like more or less. For example: more ~/.bashrc This will display one "page" (Terminal screen) of text at a time, then pause. Press space to advance to the next page, or Ctrl-c to exit more. |

You'll see the following (you may need to scroll up a bit to see the beginning):

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

#!/bin/bash

# TACC startup script: ~/.bashrc version 2.1 -- 12/17/2013

# This file is NOT automatically sourced for login shells.

# Your ~/.profile can and should "source" this file.

# Note neither ~/.profile nor ~/.bashrc are sourced automatically

# by bash scripts.

# In a parallel mpi job, this file (~/.bashrc) is sourced on every

# node so it is important that actions here not tax the file system.

# Each nodes' environment during an MPI job has ENVIRONMENT set to

# "BATCH" and the prompt variable PS1 empty.

#################################################################

# Optional Startup Script tracking. Normally DBG_ECHO does nothing

if [ -n "$SHELL_STARTUP_DEBUG" ]; then DBG_ECHO "${DBG_INDENT}~/.bashrc{"; fi

##########

# SECTION 1 -- modules

if [ -z "$__BASHRC_SOURCED__" -a "$ENVIRONMENT" != BATCH ]; then

export __BASHRC_SOURCED__=1

module load launcher

fi

############

# SECTION 2 -- environment variables

if [ -z "$__PERSONAL_PATH__" ]; then

export __PERSONAL_PATH__=1

export PATH=.:$HOME/local/bin:$PATH

fi

# For better colors using a dark background terminal, un-comment this line:

#export LS_COLORS=$LS_COLORS:'di=1;33:fi=01:ln=01;36:'

# For better colors using a white background terminal, un-comment this line:

#export LS_COLORS=$LS_COLORS:'di=1;34:fi=01:ln=01;36:'

export LANG="C" # avoid the annoying Perl locale warnings

export BIWORK=/work/projects/BioITeam

export CORENGS=$BIWORK/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools

export BI=/corral-repl/utexas/BioITeam

export ALLOCATION=OTH21164 # For ls6 Group is G-824651

##export ALLOCATION=UT-2015-05-18 # For stampede2 Group is G-816696

##########

# SECTION 3 -- controlling the prompt

if [ -n "$PS1" ]; then PS1='ls6:\w$ '; fi

##########

# SECTION 4 -- Umask and aliases

#alias ls="ls --color=always"

alias ll="ls -la"

alias lah="ls -lah"

alias lc="wc -l"

alias hexdump='od -A x -t x1z -v'

umask 002

##########

# Optional Startup Script tracking

if [ -n "$SHELL_STARTUP_DEBUG" ]; then DBG_ECHO "${DBG_INDENT}}"; fi |

There's a lot of stuff here; let's look at just a few things.

Environment variables

The login script sets several environment variables.

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

export BIWORK=/work/projects/BioITeam

export CORENGS=$BIWORK/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools

|

Environment variables are like variables in other programming languages like python or perl (in fact bash is a complete programming language).

They have a name (like BIWORK above) and a value (the value of $BIWORK is the pathname of the shared /work/projects/BioITeam directory).

To see the value of an environment variable, use the echo command, then the variable name after a dollar sign ( $ ):

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

echo $CORENGS

|

We'll use the $CORENGS environment variable to avoid typing out a long pathname:

| Code Block | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

ls $CORENGS

|

Read more about Environment variables

Shell completion with Tab

You can use these environment variables to shorten typing, for example, to look at the contents of the shared /work/projects/BioITeam directory as shown below, using the magic Tab key to perform shell completion.

| Tip | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

The Tab key is one of your best friends in Linux. Hitting it invokes shell completion, which is as close to magic as it gets!

|

Follow along with this:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

# hit Tab once to expand the environment variable name ls $BIW # hit Tab again to expand the environment variable ls $BIWORK/ # now hit Tab twice to see the contents of the directory ls /work/projects/BioITeam/ # type "pr" and hit Tab again ls /work/projects/BioITeam/pr # type "co" and hit Tab again ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/co # type "Co" and hit Tab again ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Co # your command line should now look like this ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/ # now type "mi" and one Tab ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/mi # your command line should now look like this ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/misc/ # now hit Tab once # There is no unambiguous match, so hit Tab again # After hitting Tab twice you should see several filenames: # fastqc/ small.bam small.fq small2.fq # now type "sm" and one Tab # your command line should now look like this ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/misc/small CoreNGS ls# #type you'lla see the 3 symbolic links you just created |

Symbolic links (a.k.a. symlinks) are "pointers" to files or directories elsewhere in the file system hierarchy. You can almost always treat a symlink as if it is the actual file or directory.

| Tip |

|---|

$WORK and $SCRATCH are TACC environment variables that refer to your Work and Scratch file system areas (more on these file system areas soon). |

| Expand | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

The ln -s command creates a symbolic link, a shortcut to the linked file or directory.

period (".") then hit Tab twice again

# You're narrowing down the choices -- you should see two filenames

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/misc/small

# small.bam small.fq

# finally, type "f" then hit Tab again. It should complete to this:

ls /work/projects/BioITeam/projects/courses/Core_NGS_Tools/misc/small.fq |

Extending the $PATH

When you type a command name the shell has to have some way of finding what program to run. The list of places (directories) where the shell looks is stored in the $PATH environment variable. You can see the entire list of locations by doing this:

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ls -l shows where links go | |||

ls -l |

...

| |

echo $PATH

|

As you can see, there are a lot of locations on the $PATH.

Here's how the common login script adds the ~/local/bin directory and link a script there that we will use in the class.you created above, to the location list, along with a special dot character ( . ) that means "here", or "whatever the current directory is". In the statement below, colon ( : ) separates directories in the list. (Read more about Pathname syntax)

...

| Code Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

mkdir -p ~/local/bin

cd ~/local/bin

ln -s -f /work/projects/BioITeam/common/bin/launcher_creator.py

|

...

| |

export PATH=.:$HOME/local/bin |

...

:$PATH

|

Setting up the friendly command prompt

The complicated looking if statement in SECTION 3 of your .bashrc sets up a friendly shell prompt that shows the current working directory. This is done by setting the special PS1 environment variable and including a special \w directive that the shell knows means "current directory".

| Code Block | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cd

# hit Tab once after typing "laun"

# This will expand to launcher_creator.py

| |||||

##########

# SECTION 3 -- controlling the prompt

if [ -n "$PS1" ]; then PS1='ls6:\w$ '; fi

|